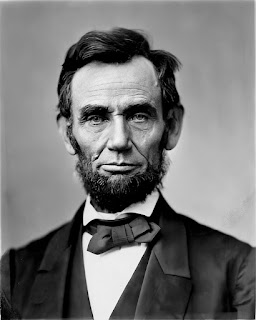

It sounds ridiculous and unnecessary, researching Lincoln and slavery. But I’m vetting American heroes with an emphasis on racism, and finding surprises and a slow evolution in Lincoln’s words and actions.

Lincoln served in the Illinois Assembly and U.S. House of Representatives as a member of the Whig Party from 1834 to 1849. He opposed both slavery and abolition, saying in 1837:

“[The] Institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy, but the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than abate its evils.”

What he did support at that time was the program of the American Colonization Society to settle freed slaves in Liberia.1

He re-entered politics in 1854 as a leader in the new Republican Party, created after the Kansas–Nebraska Act allowed slavery to expand West.2 In 1854 he said:

“If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B.—why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A?—

You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.

You do not mean color exactly?—You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own.

But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest, you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.”3 (emphasis added)

In the first Lincoln Douglas debate in 1858:

“I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the Black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which in my judgment will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong, having the superior position.”4 (emphasis added)

But at the same time he noted privately:

“As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this, to the extent of the difference, is no democracy.”5

The conclusion is that Lincoln personally opposed slavery, but was willing to publicly tolerate it in the South. His primary goal was to preserve the Union, and he was willing to continue slavery for that. In an 1862 letter to the editor of the New-York Tribune, Horace Greeley, he wrote:

“If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. . . I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.”6

Lincoln eventually issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in the Confederacy. He pushed the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in all the United States, and recommended extending the vote to African Americans.7

But as Frederick Douglass said at the dedication of The Freedmen’s Monument in Lincoln Park, Washington, DC in 1876:

” . . . even here in the presence of the monument we have erected to his memory, Abraham Lincoln was not, in the fullest sense of the word, either our man or our model. In his interests, in his associations, in his habits of thought, and in his prejudices, he was a white man. He was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men.He was ready and willing at any time during the first years of his administration to deny, postpone, and sacrifice the rights of humanity in the colored people to promote the welfare of the white people of this country.”8(emphasis added)

Racist, or merely pragmatist? Perhaps Douglass recognized Lincoln’s slow change with his qualification of “first years”. Or maybe at the end Lincoln felt his first task was safely accomplished.

1Republican Party (United States), Wikipedia, retrieved 7/6/20.

2Abraham Lincoln, Wikipedia, retrieved 7/6/20.

3Fragment on Slavery, Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Roy P. Basler et al, The Abraham Lincoln Association, Volume 2, pp. 222-223, April 1, 1854?, retrieved 7/7/20.

4First Debate with Stephen A. Douglas at Ottawa, Illinois, Collected Works, Volume 3, pg. 16, August 21, 1858, retrieved 7/7/20.

5Definition of Democracy, Collected Works, Volume 2, August 1, 1858, retrieved 7/7/20.

6Letter to Horace Greeley, Collected Works, Volume 5, pg. 388, August 22, 1862, retrieved 7/6/20.

7Lincoln on Slavery, National Park Service, retrieved 7/6/20.

8Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, April 14, 1876.

Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.