A History of Racism, Jobs, and Resistance to Change

Recent debate over immigration and closed versus open borders raises questions about the American history of immigration. It seems that every native-born citizen is descended from immigrants; even the first Native Americans were new arrivals at some point.2 This article looks at tightening restrictions on immigration after the United States of America began in 1789.

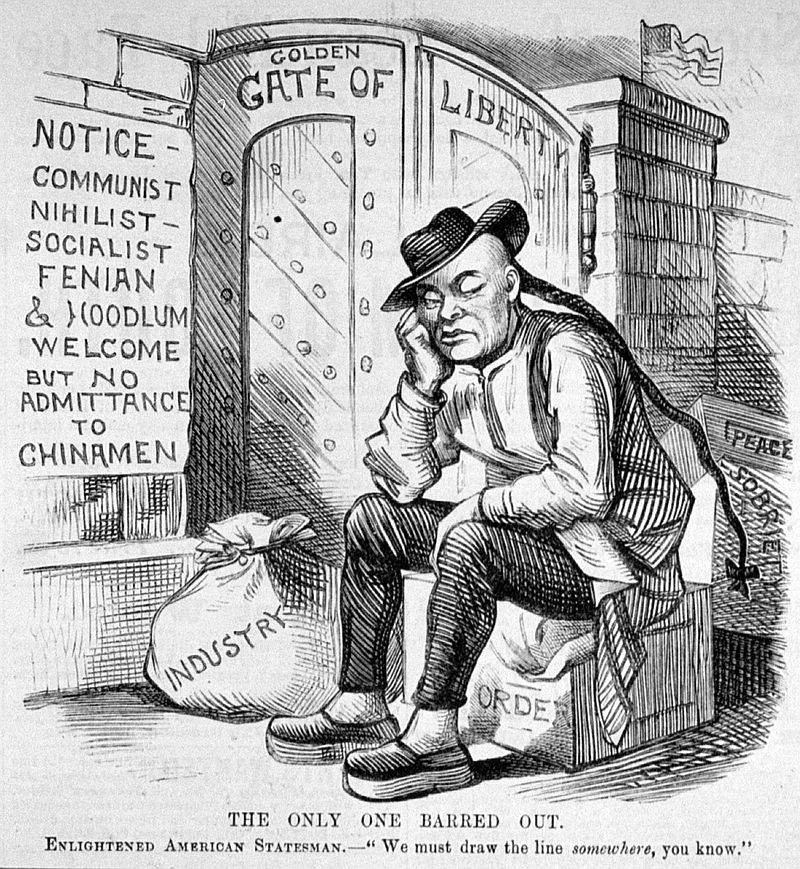

For the first 86 years there were no immigration restrictions at all. The Page Act of 1875 was the first federal immigration law and marked the end of open borders. Rep. Horace F. Page (R-CA) introduced it to “end the danger of cheap Chinese labor and immoral Chinese women.” The first Chinese immigrants to the U.S. were mostly males, arriving after 1848 as part of the California Gold Rush. The Page Act technically barred East Asian forced laborers, prostitutes, and convicts, but in practice the focus was on preventing polygamous Chinese marriage and native-born Chinese. While the number of Chinese immigrants actually increased after the Act, the female population dropped.5

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was the first U.S. law to prevent all members of a specific nationality from immigrating, banning all Chinese “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining.” The Act was upheld by the Supreme Court in Chae Chan Ping v. United States in 1889. The Supreme Court declared that “the power of exclusion of foreigners” is part of the “sovereignty delegated to the federal government by the Constitution.” Senator George Frisbie Hoar (R-MA) described the Act as “nothing less than the legalization of racial discrimination.” Labor unions supported the Act because Chinese workers were seen as responsible for low wages, and unemployment was higher for citizens than Chinese on the West Coast. The Industrial Workers of the World was the sole union exception, opposing the Act.6 The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, and a quota of 105 Chinese immigrants were allowed per year.13

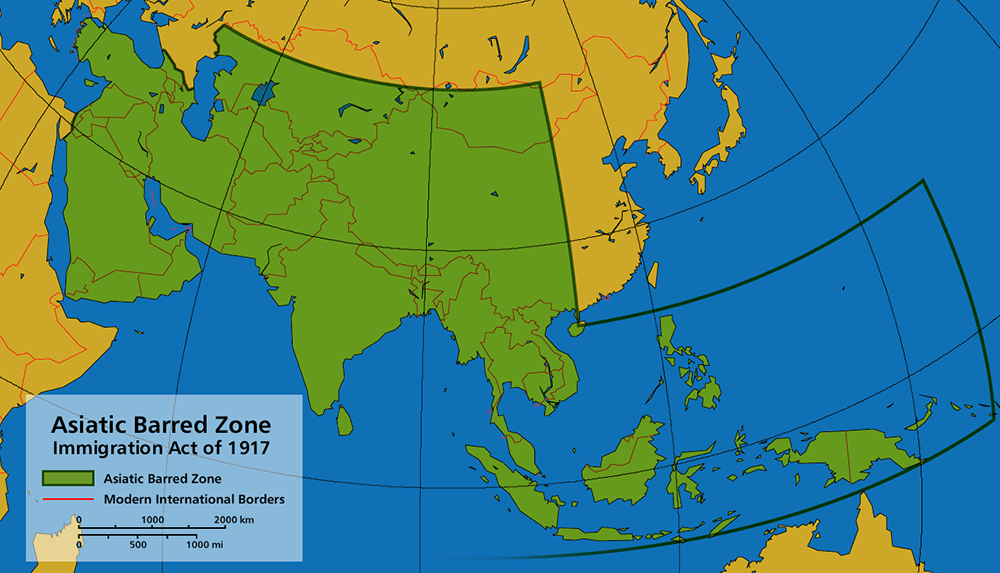

The Chinese Exclusion Act was extended by the Immigration Act of 1917, restricting immigration from an “Asiatic Barred Zone”. Much of China was omitted from the Zone, but the Act provided that “Chinese Exclusion” by previous laws was not changed. The Act also introduced a reading test for all immigrants over sixteen in their native language, with exceptions for children, wives, and elderly family members.10

If you noticed that Japan was not included in the Barred Zone, that was because the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 (日米紳士協約 Nichibei Shinshi Kyōyaku) between the United States and Japan held that the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigration, and Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States. The agreement was informal, never ratified by Congress, and ended with the Immigration Act of 1924.26

The increasing industrialization and urbanization of America in the 1880’s continued to demand labor and attract immigrants. The Immigration Act of 1891 was the first comprehensive immigration law, creating a Bureau of Immigration directed to stop or deport these “excluded” aliens:

all idiots, insane persons, paupers or persons likely to become a public charge, persons suffering from a loathsome or a dangerous contagious disease, persons who have been convicted of a felony or other infamous crime or misdemeanor involving moral turpitude, polygamists, and also any person whose ticket or passage is paid for with the money of another or who is assisted by others to come, unless it is affirmatively and satisfactorily shown on special inquiry that such person does not belong to one of the foregoing excluded classes, or to the class of contract laborers excluded by the [Alien Contract Labor Law].

It also extended federal immigration authority to land borders, stating that “the Secretary of the Treasury may prescribe rules for inspection along the borders of Canada, British Columbia, and Mexico so as not to obstruct or unnecessarily delay, impede, or annoy passengers in ordinary travel between said countries.” 9

Following World War I, both Europe and the United States were experiencing economic and social problems. The War’s destruction, the Russian Revolution, and the break up of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires in Europe increased emigration to the United States. Post-war demobilization there increased unemployment and led to an economic downturn. This combination strengthened anti-immigrant feelings in the U.S. The resulting Emergency Quota Act of 1921 added a new numerical limit on immigration by nationality: 3% of each country’s total in the 1910 census. The Act was in addition to limits by existing immigration laws and agreements, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and Asiatic Barred Zone. Professionals and those who had lived the previous year in Canada, Cuba, Mexico, or Central or South America were excepted. An unintended consequence was an increase in illegal immigration by Europeans through Canada and Mexico.11 Basing the Act on the existing population favored northern and western Europe and was an attempt to prevent change by immigration from other areas.

Practices changed with the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler Act). The Act repealed the national-origin quota system begun in 1921, started a visa system based on family reunification and skills, and set the first limits on Western Hemisphere immigration. By removing national barriers the Act ended discrimination in favor of northern and western Europeans and significantly altered U.S. demographics.16 The Immigration Act of 1990 included a diversity visa program for immigrants from under-represented countries.20

By 2001 Mexico accounted for 68% of illegal immigrants. This increased to 78% by 2005, mostly due to stricter air and sea security following the September 11, 2001 attacks.4 Our immigration restrictions have moved through racism, job protection, and maintaining the status quo. Now national security is the top justification for immigration policy.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002 made organizational changes that replaced the Immigration and Naturalization Service with three agencies in the Department of Homeland Security: Citizenship and Immigration Services (CIS), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP).23 Policy focuses on the removal of illegal immigrants, rather than security risks, in spite of national security arguments. Supporters forget that all 9/11 terrorists were foreign nationals who entered the country legally.24

Most recently we have President Trump’s third attempt to create a barred zone by Executive Order, banning the entry of nationals from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, North Korea, and Venezuela on national security grounds. It was upheld by the Supreme Court on June 26, 2018.25

| Appendix: A Chronology of U.S. Immigration Restrictions | |

|---|---|

| 1788-1789 The United States Constitution was ratified and the federal government was organized.3 | |

| 1789-1875 For 86 years the United States had laws to establish naturalized citizenship but placed no restrictions on immigration. Resident aliens could be deported under certain conditions. Citizenship was limited to whites until the Naturalization Act of 1870, which extended it to aliens of African birth or descent.4 | |

| 1875-1882 The Page Act of 1875 prohibited the entry of “undesirable” immigrants, defined as any individual from Asia coming to America as a contract laborer.5 The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years, prohibited Chinese naturalization, and provided deportation procedures for illegal Chinese.6 | |

| 1882 The Immigration Act of 1882 removed control of immigration from the states to the Secretary of the Treasury, funded federal immigration officials with a head tax on all immigrants, and excluded certain classes of immigrants landing at ports from ships: “any convict, lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.” Convictions for political offenses were excepted, and no mention was made of land borders with Canada and Mexico.7 | |

| 1885 The Alien Contract Labor Law (Foran Act) prohibited the entry of any alien under contract or agreement to perform labor in the United States, extending the Chinese Exclusion Act to all foreign contract labor. There were exceptions for temporary residents, skills not available in the US, actors, artists, lecturers, singers, servants, and family members or friends. A later amendment added exceptions for religious ministers, any “recognized profession”, and college professors.8 We have often been willing to make exceptions for immigrants with skills in demand, most recently with the H-1B visa created in 1990. | |

| 1891 The Immigration Act of 1891 was the first comprehensive immigration law, creating a Bureau of Immigration, expanding the list of “excluded” aliens, and extending federal immigration authority to land borders.9. | |

| 1907 The Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907 (日米紳士協約 Nichibei Shinshi Kyōyaku) between the United States and Japan held that the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigration, and Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States. The agreement was informal, never ratified by Congress, and ended with the Immigration Act of 1924.26 | |

| 1917 The Immigration Act of 1917 (Asiatic Barred Zone Act) restricted immigration from an “Asiatic Barred Zone”. Much of China was omitted from the Zone, but the Act provided that “Chinese Exclusion” by previous laws was not changed. The Act also introduced a reading test for all immigrants over sixteen in their native language, with exceptions for children, wives, and elderly family members.10 | |

| 1921 The Emergency Quota Act of 1921 added a new numerical limit on immigration by nationality at 3% of each country’s total in the 1910 census. The Act was in addition to limits by existing immigration laws and agreements, such as the Chinese Exclusion Act and Asiatic Barred Zone. Professionals, or immigrants who had lived the previous year in Canada, Cuba, Mexico, or Central or South America, were excepted.11 | |

| 1924 The Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act) formalized the national quota system with permanent numerical limits on immigration. It created a National Origins Formula with a total annual immigration cap of 150,000 and two categories: quota-nations and non-quota (Western Hemisphere) nations. Asian laborers were excluded, but professionals, clergy, and students were permitted.12 | |

| 1943 The Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act of 1943 (Magnuson Act) repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act and permitted Chinese nationals already in the country to become naturalized citizens. A quota of 105 new Chinese immigrants were allowed into America per year.13 | |

| 1952 The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (McCarran-Walter Act) set a quota for aliens with skills needed in the US, and increased the power of the government to deport illegal immigrants suspected of Communist sympathies.14 | |

| 1953 In Kwong Hai Chew v. Colding the Supreme Court found that the Bill of Rights did not cover immigration, but also held that when “an alien lawfully enters and resides in this country he becomes invested with the rights guaranteed by the Constitution to all people within our borders”.15 | |

| 1965 The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler Act) repealed national-origin quotas, started a visa system for family reunification and skills, set the first limits on Western Hemisphere immigration, and placed a 20,000 country limit for Eastern Hemisphere aliens.16 | |

| 1966 The Cuban Refugee Adjustment Act of 1966 exempts Cubans from any immigration quotas, from family or employment-based reasons for residency, from entering at a legal port of entry, and from the risk of being a public charge.17 | |

| 1982 In Plyler v. Doe the Supreme Court stated that illegal immigrants are “within the jurisdiction” of the states in which they reside and are under the equal protection laws of the Fourteenth Amendment.18 | |

| 1986 The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 provided amnesty to illegal aliens already in the U.S., increased border enforcement, and made it a crime to hire an illegal immigrant.19 | |

| 1990 The Immigration Act of 1990 increased legal immigration ceilings, created a diversity visa program for immigrants from “low admittance” or under-represented countries, and tripled the number of visas for priority workers and professionals with U.S. job offers.20 | |

| 1996 The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 provided phone verification for worker authentication by employers, restricted access to welfare benefits for legal aliens, and increased border enforcement. The Reed Amendment attempted to deny visas to former U.S. citizens, but was never enforced.21 | |

| 1999 In Rodriguez v. United States the United States Court of Appeals Eleventh Circuit held that laws making only specified categories of aliens eligible for Supplemental Security Income and food stamps are permitted.22 | |

| 2018 President Trump created a barred zone by Executive Order, banning the entry of nationals from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Syria, Yemen, North Korea, and Venezuela on national security grounds. The third version was upheld by the Supreme Court on June 26, 2018.25 | |

1 “Interview of Samoset with the Pilgrims,” an illustration by J. Whitney and wood engraving by Charles De Wolf Brownell (Boston, 1853). An ambassador and interpreter, Samoset (c. 1590–c. 1653) of the Abenaki people was the first Native American to greet the English Pilgrims at Plymouth and to introduce them to the Wampanoag Chief Massasoit. Volunteers for Humanity, retrieved 12/26/18.

2 When and How Did the First Americans Arrive?, Simon Worrall, National Geographic, June 9, 2018, retrieved 12/26/18.

3 United States, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/23/18.

4 List of United States immigration laws, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/23/18.

5 Page Act of 1875, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/23/18.

6 Chinese Exclusion Act, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/24/18.

7 Immigration Act of 1882, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/25/18.

8 Alien Contract Labor Law, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/24/18.

9 Immigration Act of 1891, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/24/18.

10 Immigration Act of 1917, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/26/18.

11 Emergency Quota Act of 1921, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/26/18.

12 Immigration Act of 1924, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/26/18.

13 Magnuson Act, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

14 Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

15 Kwong Hai Chew v. Colding, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

16 Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

17 Cuban Adjustment Act, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

18 Plyler v. Doe, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

19 Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

20 Immigration Act of 1990, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

21 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

22 169 F. 3d 1342 – Rodriguez v. United States, Open Jurist, March 15, 1999, retrieved 12/27/18.

23 United States Department of Homeland Security, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/27/18.

24 Post-9/11 Policies Dramatically Alter the U.S. Immigration Landscape, Muzaffar Chishti and Claire Bergeron, Migration Policy Institute, September 8, 2011, retrieved 12/27/18.

25 Trump’s Travel Ban: How It Works and Who Is Affected, Rick Gladstone and Satoshi Sugiyama, New York Times, July 1, 2018, retrieved 12/27/18.

26 Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907, Wikipedia, retrieved 12/28/18.

Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.