Then move your family westward,— The American Songbag,

Good health you will enjoy,

And rise to wealth and honour

In the state of El-a-noy.

Carl Sandburg, 1927

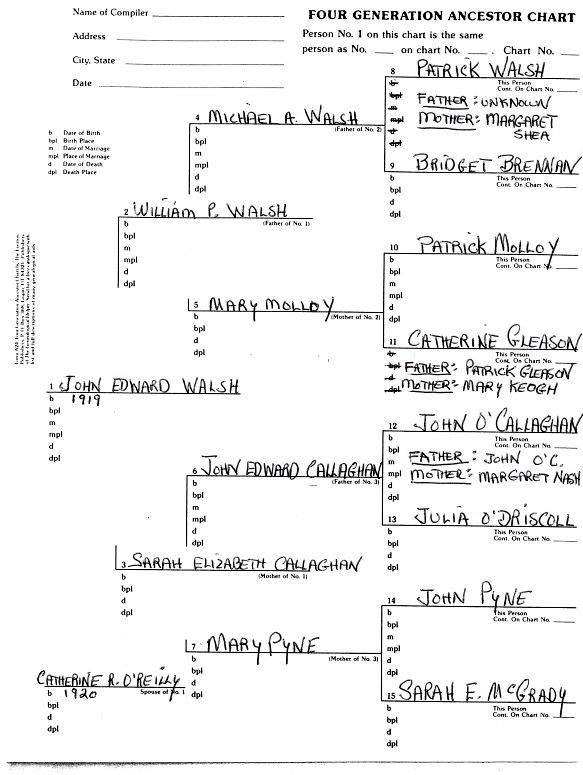

In 1819 Patrick Walsh is born in the village of Cooleyhune, rural County Carlow, Ireland. Twelve years later Bridget Brennan is born in the Carlow village of Guellan.

Navan & District Historical Society

From the 12th-Century Anglo-Norman invasion to the 17th Century defeat of the Irish earls by Queen Elizabeth I, England had struggled to subdue the recalcitrant Irish. By the mid 1600’s three-fourths of Irish lands had been given to Protestant loyalists, many of them absentee landlords in England. The Penal Laws of 1695 barred Catholic Irish from worship, teaching, trade, and professions. Limited to tenant farming, the Irish were force to subdivide farms into smaller and smaller parcels.1

By the 1840’s almost half the farms in Ireland were less than five acres in size, too small for more than subsistence farming of potatoes. In 1846 the British Corn Laws were abolished, Irish grain lost its favored status in British markets, employment on larger farms declined, and landlords turned tenant farms to pasture. “The average farmer could achieve a higher standard of living only by giving up farming in Ireland.2

To these economic conditions was added the fungus Phytophthora infestans, the potato blight. Appearing first in North America, it reached Ireland in September of 1845, destroying potato crops in half the island. Between 1845 and 1852 there were complete or partial crop failures every year, and one million people died of starvation, typhus, cholera, and other diseases.3

In 1847 Bridget’s family decides to leave Guellan for America. Her father Patrick buys tickets, only to see his wife Ann fall ill and die of a fever. At the urging of 15 year-old Bridget, Patrick leaves the children in her care and sets off alone. Bridget has contracted the fever from nursing her mother, and after she falls ill the children are taken in by Aunt Mary Fenlon until she recovers.

The typical Irish famine immigrant was an unskilled farm worker without capital and accustomed to meager living conditions. They tended to be Catholic, English-speaking, literate, and politically educated by nationalist movements. If not traveling with family, they would be working to earn passage for relatives, and often living with others from their Irish village.4

In 1847 Patrick Brennan arrives in New York City, 39 years before the Statue of Liberty and 45 years before Ellis Island. He probably lands at Manhattan on an East River dock near South Street, since the Emigrant Landing Depot at Castle Garden was not opened until 1855. He finds work on a farm in Hoosick Falls, New York, north of Albany.

The following year Patick Walsh leaves Cooleyhune for America. His port of enty is also New York, and he obtains work with his brother Michael on a farm near White Creek and Hoosick Falls.

Patrick Brennan sends for his three older children, and Bridget and her two brothers arrive in New York on June 5, 1849. The seventeen year-old Bridget finds work near her father, as a companion to an invalid woman for 75 cents a week.

Between 1846 and 1855 twenty thousand people (almost one in four) left County Carlow. This was part of the two million (one in five) who left Ireland during that time.5 In 1850 44% of all foreign-born residents in the United States were Irish. The Irish were the largest of all immigrant groups in the 1850 and 1860 censuses.6

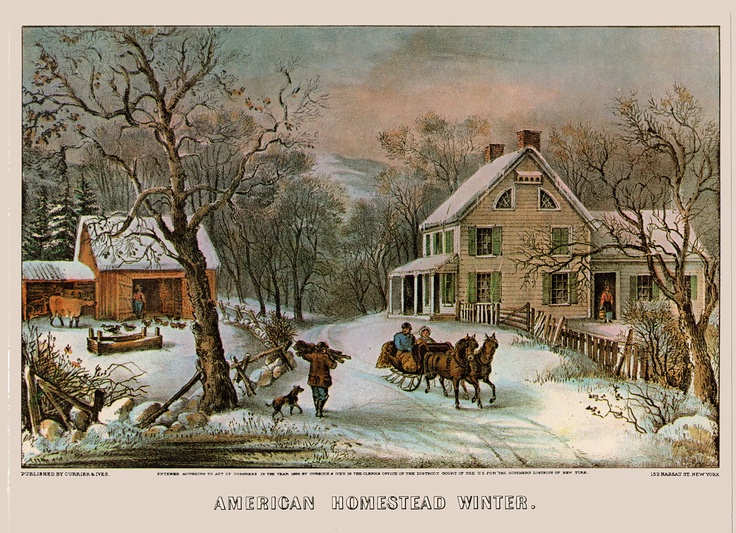

That Christmas Patrick Brennan hires a sleigh to take the family to church in White Creek. The sleigh breaks down, and the Brennans warm themselves in a nearby farm house where Bridget meets Patrick Walsh. Patrick and Bridget are married in White Creek on January 11, 1852 by a traveling priest from Schaghticoke, New York. Patrick is 32 and Bridget is 20.

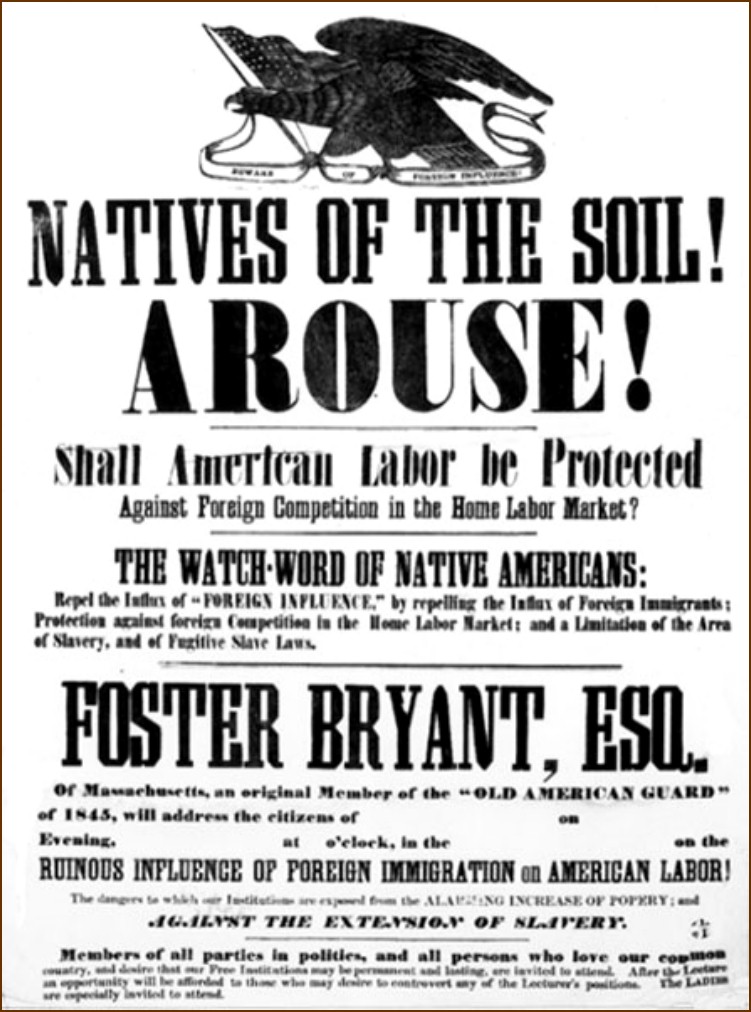

The Irish in America were attacked for their poverty, religion, and numbers. In 1835 the Native American Party had formed “in defence of American institutions against foreign influence,” specifically the Irish. Its national convention in 1845 supported repeal of the naturalization laws for granting citizenship and limiting public office to native Americans.

The “Supreme Order of the Star Spangled Banner” was formed in 1850 to repeal state suffrage laws and Federal land grants for unnaturalized residents. The group became best known as the Know-Nothings, from members of the semi-secret society answering all questions with the phrase “I don’t know.”7

There were anti-Catholic riots in Philadelphia, Richmond, and Charleston in 1844 to 1845, with churches and convents looted and burned, and deaths from street fighting. Similar outbreaks in New York were prevented only by organized defense groups and existing Irish-American political strength.8

Living with the newlyweds are Bridget’s two younger sisters, her father Patrick, and Patrick Walsh’s mother. Patrick Brennan urges settling “new” country, and the household moves to Springfield, Illinois in 1853.

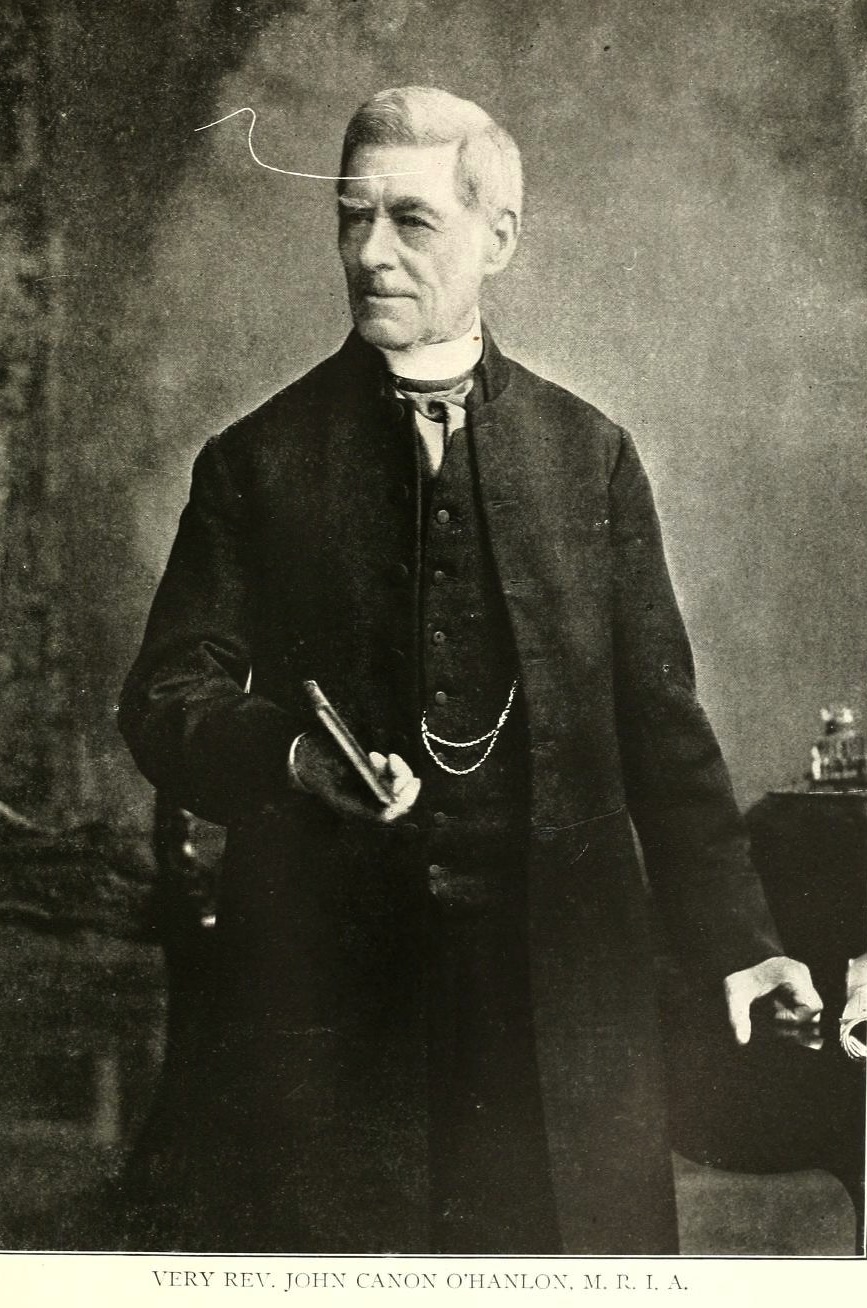

The Irish Emigrants Guide for the United States (1851) by Rev. John O’Hanlon described Illinois as having “soil of surpassing fertility” and “a most liberal constitution in reference to naturalized citizens. It is free.”9 O’Hanlon ended each description of the 31 existing states with the label “free” or “slave state.” Irish immigrants settled overwhelmingly in free states, and in 1860 only 13% of all foreign-born residents lived in slave states.10 Whether the choice was philosophical or practical and economic probably depended on the individual.

Patrick Walsh works in a slaughter house, contracts rheumatism, and cannot work for a year. Mary and Michael Walsh are born. The family moves to Cottage Gardens, a large truck farm in Springfield where Patrick works and Ann is born. They move again to Irish Grove, Illinois, where Patrick works in a brickyard. The family keeps a garden, some chickens, a calf, and a pig. They begin to sell vegetables, eggs, butter, and an occasional pig or hen in the Springfield market.

Patrick sells all their stock to buy a team of horses for $120, and rents forty acres in Menard County, Illinois. When one horse dies, he goes into debt buying one and then two replacements. A year later they repay the debt and rent eighty acres in adjacent Logan County. Kate, Matthew, Margaret, and Patrick, Jr. are born. There are now three sons and four daughters in the family.

In 1868 Patrick Walsh and a neighbor, Dennis Sullivan, travel to Champaign County, Illinois to buy land. Each mortgages eighty acres in Ludlow Township for $13 an acre, or $1,040. Patrick and Dennis build a 32 by 16 foot cabin and return to Springfield for their families.

Stephen Byrne discussed Illinois real estate in his 1873 guide for Irish immigrants:

“Land is, in general, dear, ranging from ten to two hundred dollars an acre. Not much land is to be had at the first-named price. . . There is hardly a State in the Union in which Irish people are in so prosperous a condition as in this. It is easily accounted for by the fact that large numbers of them purchased land several years ago from the railroad companies for a low price and on a long credit.”11

On March 1, 1869 the Walsh and Sullivan families set off for Champaign County. They travel in farm wagons with their livestock alongside, chopping ice to ford the Sangamon River. Bridget, described as “frail,” follows later by train with sixteen year-old Mary and two younger children.

The two families divide the cabin with a chalk line on the floor, and any child who misbehaves at the neighbor’s is promptly sent home. Twenty days after leaving Champaign, Bridget gives birth to Johanna, her eighth child. She is attended by her sixteen year-old daughter Mary, and Mrs. Sullivan. A week later Mrs. Sullivan gives birth, attended by Bridget and Mary Walsh.

Patrick and Bridget remained on that homestead for the rest of their lives. In 1893, after twenty-five years in Ludlow, Bridget dies of pneumonia at the age of 62. Patrick dies six years after at the age of 81.12

Then move your family westward,— “El-a-noy” 13

Bring all your girls and boys,

And cross at Shawnee Ferry

To the state of El-a-noy.

1 Marjorie R. Fallows, Irish Americans, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1979, pp. 12-16.

2 Fallows, pp. 16-24.

3 Oliver MacDonagh, “The Irish Famine Emigration to the United States,” American Immigration & Ethnicity, Vol. 2, George E. Pozzetta, ed. Garland Publishing, New York, p. 407.

4 MacDonagh, pp. 428-432.

5 MacDonagh, pp. 420-421.

6 Lawrence Guy Brown, Immigration: Cultural Conflicts and Social Adjustments, Longmans, Green, New York, 1933, p. 81.

7 Brown, pp. 94-101.

8 MacDonagh, p. 434.

9 John O’Hanlon, The Irish Emigrants Guide for the United States (1851), Edward J. Maguire, ed. Arno Press, New York, 1976, p. 205.

10 Brown, p. 91.

11 Stephen Byrne, Irish Emigration to the United States (1873), Arno Press, New York, 1969.

12 The family histories of Ann Walsh Murray, Johanna Walsh McCabe, Florence McCabe Nelson, and Brian Michael Walsh, 1983.

13 The song “El-a-noy” is from The Folk Songs of North America, Alan Lomax, Doubleday, 1960. The tune is from the Gaelic song “The Bog Deal Board.”

Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.